The new Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor Strategy has engaged hundreds of community members as part of its planning process to position the 13 UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Global Geoparks and Biosphere Regions on the world stage.

Introduction

In June 2023, Destination Canada launched the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program to contribute to a more resilient tourism industry through accelerated destination development of corridors across Canada. Tapping into the momentum of tourism for good and more regenerative and holistic approaches, the Program set out to redefine collaboration by working across boundaries with new and existing partners. As one of three projects selected as a pilot, the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor emerged for its compelling set of natural landscapes, historical sites, diverse cultural heritage and communities with the potential to foster innovation and reimagine their future.

Weaving through the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador, the corridor

As implementation of the strategy begins in the three provinces, the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor is setting an example as it becomes a globally recognized journey, ensuring that as residents and visitors explore these sites, the environmental beauty and integrity and the stories of people and place are celebrated and protected for future generations.

The UNESCO Sites

“A journey through the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor is like a journey through a book of meaningful stories for humanity”, says Jennifer Dingman, Executive Director for the UNESCO-designated Fundy Biosphere Region and Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark and a project lead for the corridor planning work. “Each UNESCO site is a chapter in a story that speaks to the rich culture and natural history of the region.” Together, the 13 sites serve as windows into a billion years of change and offer experiences that are as diverse as they are profound.

Visitors to the corridor can hike to ancient fossilized trees and kayak the world’s highest tide on the same day. Viking settlements, quiltwork of agricultural marvels, and a 500-year-old whaling station are among other experiences already available. Between iceberg watching and puffin sightings, visitors have access to jaw-dropping cliffs, dark sky preserves, and some of the most picturesque towns on North America’s eastern seaboard. Visitors will also discover 10,000 years of

These 13 sites are an opportunity to intentionally develop tourism in the surrounding communities. “If you enhance Red Bay and get more visitors that will provide more opportunities for businesses in all the region,” says Philip Bridle, Visitor Experience Team Leader at the Red Bay Basque Whaling Station UNESCO World Heritage Site. “We’re the drawing card and we are free advertising for other communities.” As early as 1530, Red Bay was home to Basque whaling operations, where a ship fully loaded with whale oil was valued at almost $40 million in today’s dollars. Philip recognizes how a collaborative effort will benefit his site, saying “We have limited capacity. The transportation system and accommodations can’t handle a lot more visitors than we are getting.” Organizing the 13 sites into a corridor means Red Bay, along with the other 12 UNESCO sites, has access to planning, infrastructure initiatives, funding, and other opportunities that the site wouldn’t be able to access by themselves.

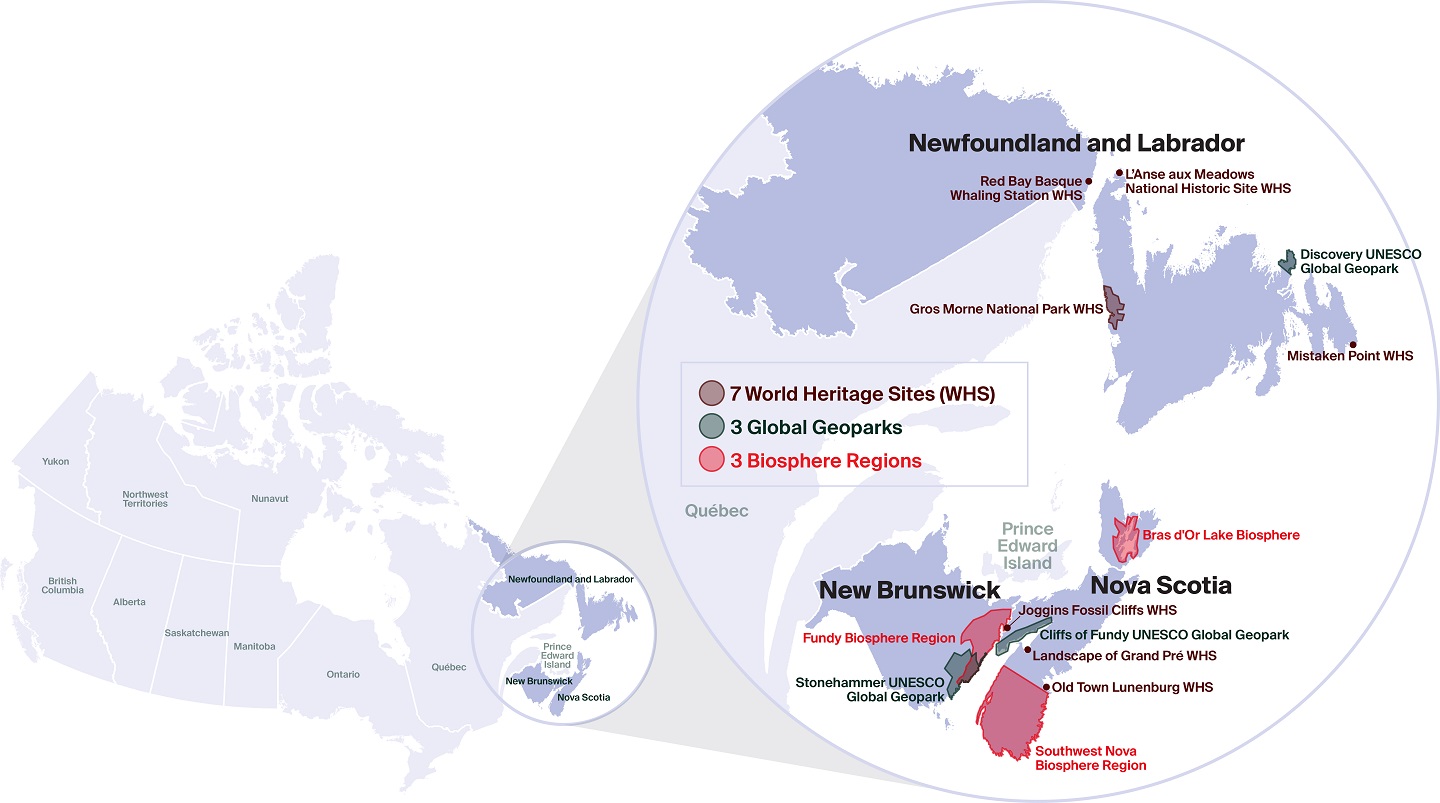

The Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor contains 13 remarkable sites throughout Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador, each considered to be of worldwide importance.

World Heritage Sites (WHS): UNESCO designated places of outstanding universal value to humanity, protected for future appreciation.

Geoparks: UNESCO designated unified areas where significant geological sites are protected, educated about, and developed sustainably.

Biosphere Regions: UNESCO designated areas for testing approaches to manage social and ecological systems interactions.

They are:

- Bras d’Or Lake Biosphere Region (Nova Scotia)

- Cliffs of Fundy UNESCO Global Geopark (Nova Scotia)

- Discovery UNESCO Global Geopark (Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Fundy Biosphere Region (New Brunswick)

- Gros Morne National Park (Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Joggins Fossil Cliffs World Heritage Site (Nova Scotia)

- L’Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site (Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Landscape of Grand Pré World Heritage Site (Nova Scotia)

- Mistaken Point World Heritage Site (Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Old Town Lunenburg World Heritage Site (Nova Scotia)

- Red Bay Basque Whaling Station World Heritage Site (Newfoundland and Labrador)

- Southwest Nova Biosphere Region (Nova Scotia)

- Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark (New Brunswick)

Aligning with Regenerative Principles

Destination Canada’s Tourism Corridor Strategy Program places an emphasis on regenerative principles and evolving community-led destination development. The Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor is community-driven and rooted in regenerative tourism principles. This model seeks to revitalize the regional environment and the communities within it through the power of tourism.

Being part of the international UNESCO family means working towards the regenerative values of making a place better by taking action on protected areas, education, climate change, conservation, sustainable development and sustainable tourism. The corridor aims to uphold these commitments while showcasing the 13 UNESCO sites to the world as an example of tourism-done-better.

These regenerative tourism principles are foundational for many of the region’s tourism businesses and this corridor work is an invitation to inspire others to follow. Tim Doucette of the Deep Sky Eye Observatory and the Starlight Development Society in Nova Scotia built a regenerative business model from the ground, up: legally blind, Tim developed a knack for stargazing, and after playing a fundamental role in the establishment of “Acadian Skies & Mi’kmaq Lands”—North America’s first and only Starlight Tourism Destination—he began to work on curbing the growing light pollution that is threatening the night sky.

“It has to be addressed sooner rather than later,” says Tim of the light pollution that is already impacting his tourism business. “It has slowly increased with the advance of LED lights and population growth. Once you can guarantee the protection of the night sky through education and legislation, you can advertise it for what it is: dark skies.”

The regenerative tourism principles embedded within the corridor planning process aimed to ensure that the corridor focusses on host experiences that are memorable for visitors, enriching and empowering for the local communities, and beneficial for the environment. This approach aligns with the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), UNESCO priorities and Indigenous ways of being, ensuring that the development and operation of the corridor contributes to global efforts towards regeneration. For Tim and his team, collaborations with the Town of Yarmouth are helping to protect the night skies that are drawing visitors to the Southwest Nova UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

Engaging the Spirit of Collaboration

At its heart, the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor is a collaborative effort. In bringing together the 13 UNESCO sites, this project has connected people throughout Atlantic Canada and across the country. By asking questions through workshops and surveys such as “What are the benefits of having the UNESCO site(s) in your territory?” and “What would your ideal vision for the visitor economy in the corridor look like 10 years from now?” community members began sharing new ideas for inspiring ways forward.

To deepen understanding of tourism in the corridor, key partners on the project encompassed a range of organizations at varying levels and areas of expertise: Destination Canada, the Canadian Commission for UNESCO, and the Fundy UNESCO Biosphere Region & Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark, Parks Canada, the UNESCO sites, the governments of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador and tourism consultancy firm Vardo Creative. The Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada and the provincial Indigenous tourism associations also contributed alongside operators and organizations inside and outside the tourism industry.

From the local business community, Marieke Gow of the Artisan Inn & Twine Loft Dining in Trinity, Newfoundland has long believed in the region’s potential as a major tourism corridor. “Every community is worth seeing… Over the past 15-20 years and especially in the past five years a lot of the communities on the Bonavista Peninsula have started developing… each is known for their own thing.”

A comprehensive engagement process helped ensure input from each of these unique community perspectives. During the planning phase, dozens of community members on the front lines of tourism in Atlantic Canada, including staff and volunteers at all 13 sites, added their passionate voices to inform the plan’s direction. This was amplified by over 470 thoughtful engagement survey responses representing every corner of the corridor region, over 80 interviews and input from over 70 people from over 50 organizations who participated in workshops.

“People are inspired and see the potential of this UNESCO Corridor really benefiting their communities,” says Erica D’Souza of Destination Canada. “We’ve been so inspired by how engaged and open everyone has been with contributing forward-thinking ideas and sharing their knowledge and perspectives.”

Marieke is one of those engaged leaders. “We have an opportunity to prepare for a potential influx of tourists,” she says of the corridor. “We want this place to be as pristine as it is now even as we embrace an influx of tourism to contribute to the growth of the economy.”

The engagement process has been multifaceted, ensuring findings are validated with data and insights and strengthened and vetted with the community members they are intended to benefit. For example, six smaller Advisory Groups were formed to ensure the strategy was reviewed by a diversity of community members who understand and consider the needs and health of the whole corridor and can help harmonize what is truly meaningful. Advisory Groups helped validate and refine the strategies, actions and financial requirements. An Indigenous Advisory Group focused on building Indigenous relationships and understanding the path to respectful and regenerative Indigenous tourism development.

The impact of this collaboration will ensure the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor is not just a pathway through the provinces but a collective journey, crafted and enriched by the various people that call it home.

The Power to Transform

The Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor can be a positive force of transformation for local communities, including opportunities to develop shoulder- and off-season experiences. This might include increasing the availability of guided ecotours within the 13 sites, reviewing policies to look at reducing barriers for seasonal accommodations such as research cabins, or developing a corridor-wide event to support seasonal extensions into Fall, such as an arts crawl that captures the beauty of the UNESCO sites. These initiatives can attract visitors year-round, create jobs and contribute to vibrant communities while mitigating the pressures and challenges associated with peak season tourism.

The geographic distribution of summer travellers is a parallel opportunity. By encouraging visitors to travel the length of the corridor to less familiar places through, for example, a Site Passport program, the benefits of tourism would reach more communities and cultivate new economic prosperity. The corridor’s planning provided an opportunity to brainstorm and identify the steps necessary to make this possible, while determining the levers such as funding and investment attraction required to make progress and create change.

Another pivotal opportunity identified throughout the Corridor is attracting high-value guests (HVGs) to build local visitor economies while supporting community values and protecting ecological integrity. By attracting investors and entrepreneurs with shared visions and goals, building and developing the right infrastructure and experiences, and showcasing the sites in a manner that is aligned with regenerative principles, the corridor has the potential to attract visitors whose explorations would contribute towards the economic, social, and environmental wealth and wellbeing of residents. This may prove key for sites that have more room to grow, such as Red Bay Basque Whaling Station World Heritage Site.

From the vantage point of entrepreneurs developing their own tourism experiences, Laurie Currie of Local Guy Adventures sees a world of untapped potential in the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor, particularly when it comes to crafting authentic, immersive, and distinctly Canadian experiences for visitors. “You could have a nice open fire on the beach after catching scallops, picking fiddleheads on the salt marsh. People would love that coming from anywhere... I’m looking to get wooden barrels made so we could do salt-water seaweed baths.”

These unique experiences reflect a deep-seated appreciation for the natural wonders of the region. Laurie’s vision hints that the true value of these 13 sites lies not just in their natural and cultural assets, but also in the authentic, immersive experiences they can offer to visitors from around the world. “How about floating tents up on the Bay of Fundy? Wouldn’t that be cool! And feel the rise of the world’s highest tides.”

A Journey into the Future

Destination Canada President and CEO Marsha Walden said of the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program, “[It] will help to fill the existing gap in cross-boundary, intentional, destination development and ultimately help build a more resilient tourism industry that contributes to the wealth and wellbeing of Canadians.”

The Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor has the potential to become a leading case study for future destination development projects as it brings together local cultures, incredible experiences, and undiscovered natural beauty into a seamless journey.

As the corridor showcases the 13 UNESCO sites, it also models regenerative approaches to tourism, ensuring that the exploration and enjoyment of these wonders do not come at a burden to the local community and the sites themselves. It is expected that the transformative power of the corridor, with the continued support and engagement from partners and the community, will be felt in a positive way for the long-term.

And as the destination gets ready for the world stage, Laurie Currie captures the excitement of visitors, residents, investors, and other partners alike: “What are we waiting for?”

Stay Informed

Community members, interested investors, rights holders, stakeholders and partners can reach out to the Atlantic Canada UNESCO Tourism Corridor planning team here:

Erica D'Souza

Senior Program Manager, Destination Development

Destination Canada

dsouza.erica@destinationcanada.com

Zoe Compton

Programme Officer, Natural Sciences

Canadian Commission for UNESCO

Zoe.Compton@ccunesco.ca

Jennifer Dingman

Executive Director

Fundy Biosphere Region & Stonehammer UNESCO Global Geopark

Executive.Director@fundy-biosphere.com