Field to Fork: SK MB Agritourism

Overview

“Offering farm-to-table dining and sustainable farming experiences in the breadbasket of the world.”

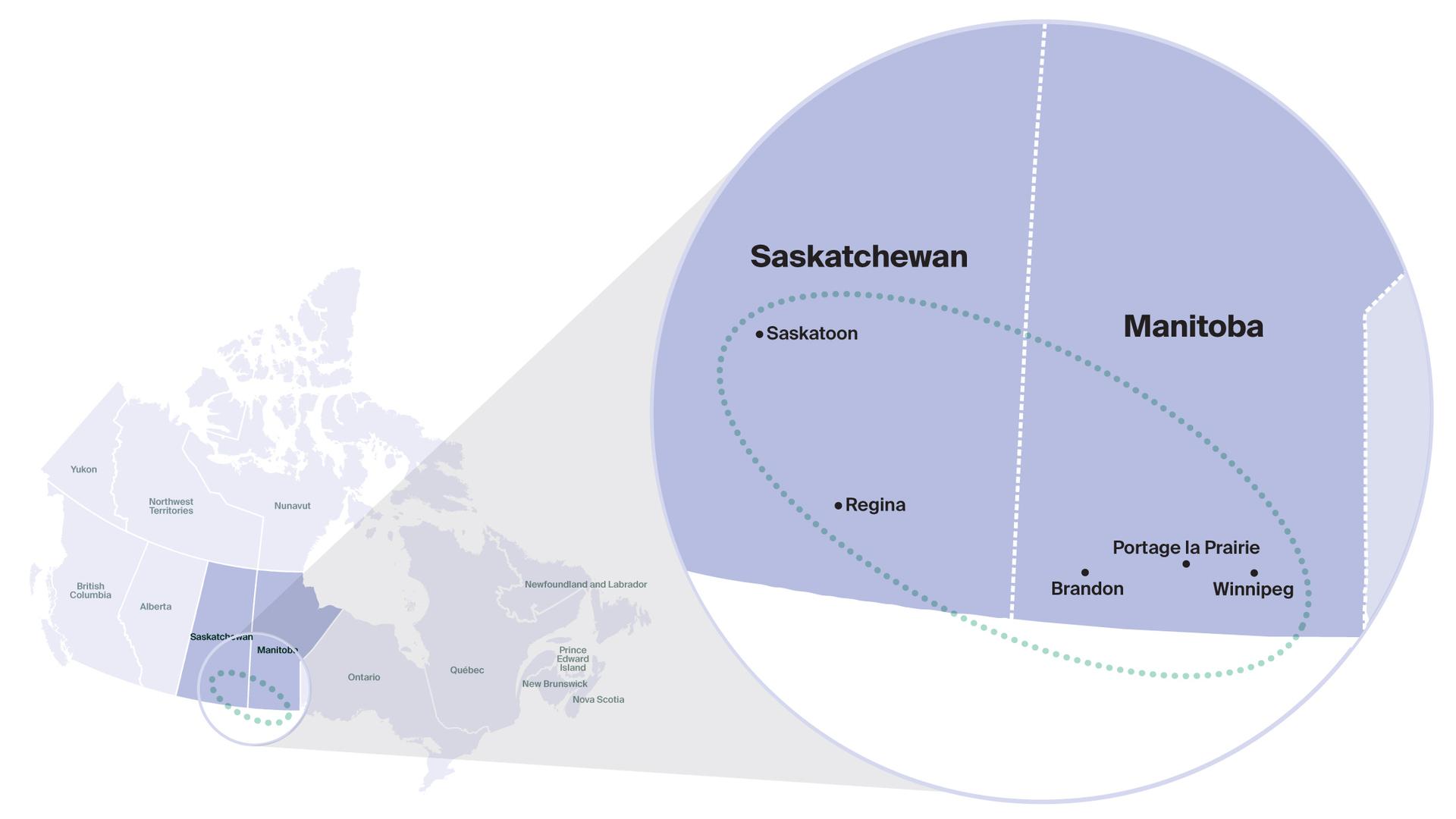

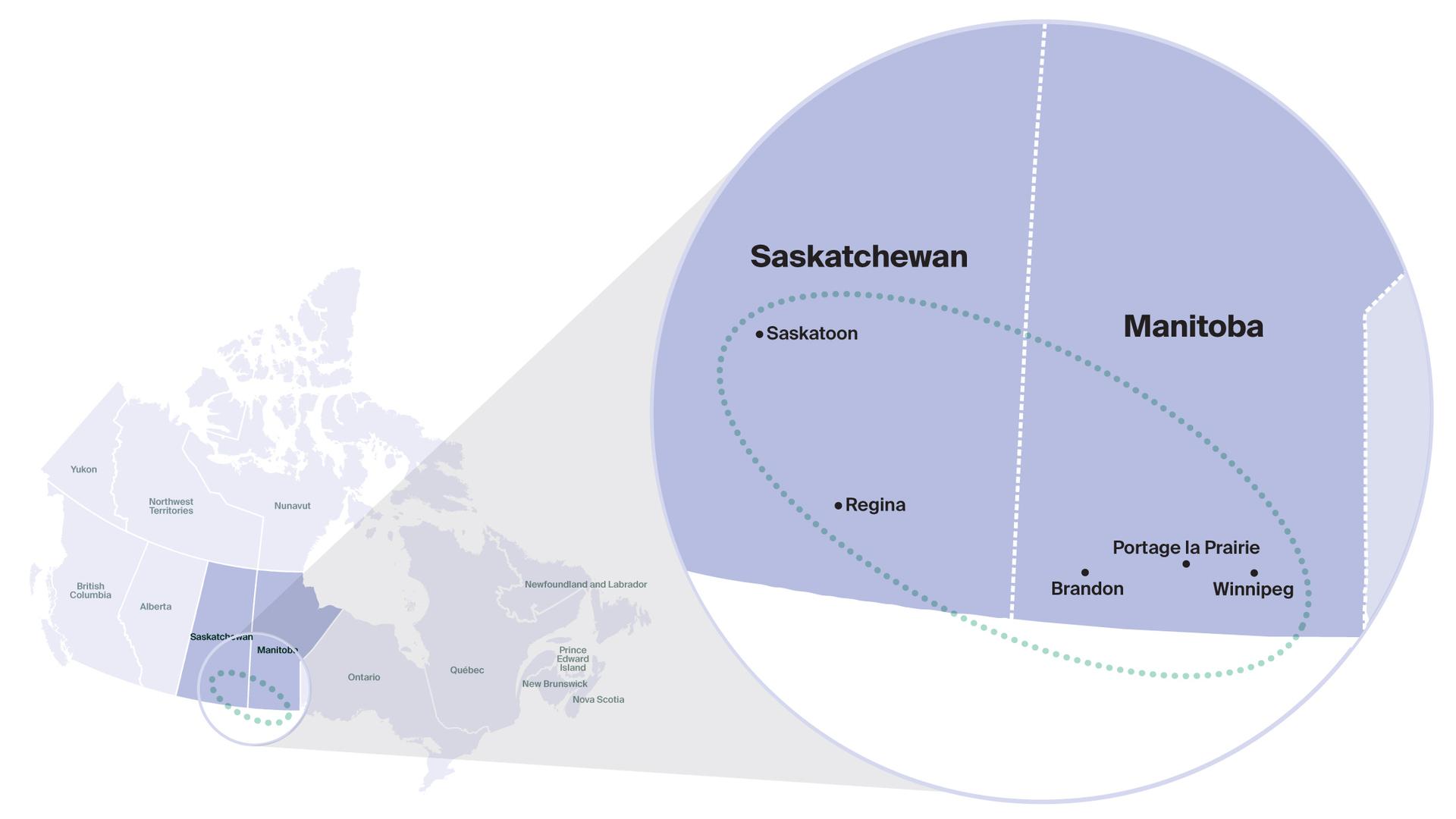

The Field to Fork: Saskatchewan Manitoba Agritourism corridor leverages the region's status as one of the world's largest and most productive agricultural areas to position Saskatchewan and Manitoba as global leaders in agritourism. This corridor aims to showcase the provinces' thriving agriculture sectors while offering visitors unique and engaging experiences that highlight the journey from field to fork.

As Destination Canada's first corridor with a culinary focus, Field to Fork connects major gateway cities including Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, and Regina. The corridor offers a diverse range of experiences such as farm stays, festivals, farmers' markets, farm-to-table culinary experiences, Indigenous agritourism, and tours of breweries and distilleries.

Overview

“Offering farm-to-table dining and sustainable farming experiences in the breadbasket of the world.”

The Field to Fork: Saskatchewan Manitoba Agritourism corridor leverages the region's status as one of the world's largest and most productive agricultural areas to position Saskatchewan and Manitoba as global leaders in agritourism. This corridor aims to showcase the provinces' thriving agriculture sectors while offering visitors unique and engaging experiences that highlight the journey from field to fork.

As Destination Canada's first corridor with a culinary focus, Field to Fork connects major gateway cities including Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, and Regina. The corridor offers a diverse range of experiences such as farm stays, festivals, farmers' markets, farm-to-table culinary experiences, Indigenous agritourism, and tours of breweries and distilleries.

Rationale

- Alignment with Economic Sector Strategy: The corridor supports Destination Canada’s Business Events Strategy by leveraging visitation from international conferences into pre- and post-event tours, enhancing the region's economic impact.

- Support for Federal Tourism Growth Strategy (FTGS): The corridor aligns with the FTGS's emphasis on increased festivals and events, particularly in the agritourism sector.

- Indigenous Tourism Integration: The corridor incorporates Indigenous agritourism offerings, supporting cultural preservation and economic development in Indigenous communities.

- Showcase of Agricultural Leadership: The corridor highlights Saskatchewan and Manitoba's status as global leaders in agriculture, positioning the region as a premier agritourism destination.

- Promotion of Culinary Tourism: By offering farm-to-table dining experiences and showcasing local ingredients, the corridor supports the growing trend of culinary tourism.

Rationale

- Alignment with Economic Sector Strategy: The corridor supports Destination Canada’s Business Events Strategy by leveraging visitation from international conferences into pre- and post-event tours, enhancing the region's economic impact.

- Support for Federal Tourism Growth Strategy (FTGS): The corridor aligns with the FTGS's emphasis on increased festivals and events, particularly in the agritourism sector.

- Indigenous Tourism Integration: The corridor incorporates Indigenous agritourism offerings, supporting cultural preservation and economic development in Indigenous communities.

- Showcase of Agricultural Leadership: The corridor highlights Saskatchewan and Manitoba's status as global leaders in agriculture, positioning the region as a premier agritourism destination.

- Promotion of Culinary Tourism: By offering farm-to-table dining experiences and showcasing local ingredients, the corridor supports the growing trend of culinary tourism.

Key attractions and experiences

- Savoring Indigenous cuisine through authentic dining experiences

- Exploring agritourism offerings, including honey production and berry picking

- Indulging in farm-to-table culinary experiences showcasing local ingredients

- Participating in unique winter activities, such as ice fishing in specially designed villages

- Discovering the beauty and art of flower farming through workshops and tours

- Immersing in rural charm and local products at country markets and farms

- Experiencing innovative winter dining concepts that showcase the region's culinary creativity

- Tasting craft beers inspired by Indigenous recipes and traditions

- Learning about Indigenous history and agricultural practices at cultural centers and museums

- Staying in unconventional accommodations that reflect the region's agricultural heritage

- Experiencing French-Canadian culture through local events and festivals

Key attractions and experiences

- Savoring Indigenous cuisine through authentic dining experiences

- Exploring agritourism offerings, including honey production and berry picking

- Indulging in farm-to-table culinary experiences showcasing local ingredients

- Participating in unique winter activities, such as ice fishing in specially designed villages

- Discovering the beauty and art of flower farming through workshops and tours

- Immersing in rural charm and local products at country markets and farms

- Experiencing innovative winter dining concepts that showcase the region's culinary creativity

- Tasting craft beers inspired by Indigenous recipes and traditions

- Learning about Indigenous history and agricultural practices at cultural centers and museums

- Staying in unconventional accommodations that reflect the region's agricultural heritage

- Experiencing French-Canadian culture through local events and festivals

Partner organizations

- Travel Manitoba

- Tourism Saskatchewan

- Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada

- Indigenous Tourism Manitoba

- Culinary Tourism Alliance

- Local economic development organizations (Economic Development Winnipeg, Brandon Tourism, and others)

- Provincial agriculture ministries

- Regional agricultural associations

Partner organizations

- Travel Manitoba

- Tourism Saskatchewan

- Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada

- Indigenous Tourism Manitoba

- Culinary Tourism Alliance

- Local economic development organizations (Economic Development Winnipeg, Brandon Tourism, and others)

- Provincial agriculture ministries

- Regional agricultural associations

Current status and updates

Planning partners are developing the strategy, which aims for completion by December 2025.

Find the latest updates here.

Current status and updates

Planning partners are developing the strategy, which aims for completion by December 2025.

Find the latest updates here.

Testimonials

"Manitoba is known as the breadbasket to the world. Our agricultural roots helped build our province's economy and continued innovation has created new opportunities for exploration and growth."

- The Honourable Glen Simard, Minister for Sport, Culture, Heritage and Tourism, Province of Manitoba

"We're grateful to Destination Canada for its support in developing agritourism as a sustainable contributor to local economies throughout Canada."

- Colin Ferguson, President & CEO, Travel Manitoba

"This Field to Fork concept will generate a new, sustainable level of tourism that, in my opinion, could rival any agritourism sector around the world."

- Lanny Stewart, Director of Marketing & Communications, Brandon Tourism

"The Field to Fork Agritourism venture is an effective avenue for showcasing Indigenous history and traditional ways of life. The inclusion of Indigenous communities and entrepreneurs presents opportunities for active engagement within the broader tourism industry, fostering partnerships and capacity building and contributing to economic development and the process of reconciliation."

- Holly Courchene, CEO, Indigenous Tourism Manitoba

"Manitoba is an agricultural powerhouse, home to more than 1,800 agricultural establishments and 13,000 sector employees... we are well positioned to develop and amplify this agritourism corridor strategy, further establishing the city as a world-class agriculture hub."

- Ryan Kuffner, President & CEO, Economic Development Winnipeg (Tourism Winnipeg)

"Thousands of farms, food processing facilities, educational institutions, agricultural events and skilled training programs provide a strong basis for further growth... By capitalizing on existing opportunities, we can significantly expand our value-added offerings, further solidifying ourselves as a top agritourism destination."

- The Honourable Jeremy Harrison, Minister Responsible for Tourism Saskatchewan

"Saskatchewan's agritourism industry is poised to grow like never before... With world-class agricultural leadership and industry strength, Manitoba and Saskatchewan have the potential to become leading agritourism destinations on a global scale."

- Jonathan Potts, CEO, Tourism Saskatchewan

"The proposed initiatives - ranging from educational programming and farm visits to unique conference itineraries and Indigenous agritourism experiences - underscore the diverse potential of our agritourism sector. We are committed to working closely with our partners to realize this vision and look forward to the positive impact it will bring to our regions."

- Steph Clovechok, CEO, Discover Saskatoon

"Together with Tourism Saskatchewan and Travel Manitoba, we're excited to showcase the region's agricultural heritage and culinary excellence while fostering a thriving, interconnected community."

- Jennifer Johnson, Deputy City Manager of Communications, Service Regina & Tourism

Testimonials

"Manitoba is known as the breadbasket to the world. Our agricultural roots helped build our province's economy and continued innovation has created new opportunities for exploration and growth."

- The Honourable Glen Simard, Minister for Sport, Culture, Heritage and Tourism, Province of Manitoba

"We're grateful to Destination Canada for its support in developing agritourism as a sustainable contributor to local economies throughout Canada."

- Colin Ferguson, President & CEO, Travel Manitoba

"This Field to Fork concept will generate a new, sustainable level of tourism that, in my opinion, could rival any agritourism sector around the world."

- Lanny Stewart, Director of Marketing & Communications, Brandon Tourism

"The Field to Fork Agritourism venture is an effective avenue for showcasing Indigenous history and traditional ways of life. The inclusion of Indigenous communities and entrepreneurs presents opportunities for active engagement within the broader tourism industry, fostering partnerships and capacity building and contributing to economic development and the process of reconciliation."

- Holly Courchene, CEO, Indigenous Tourism Manitoba

"Manitoba is an agricultural powerhouse, home to more than 1,800 agricultural establishments and 13,000 sector employees... we are well positioned to develop and amplify this agritourism corridor strategy, further establishing the city as a world-class agriculture hub."

- Ryan Kuffner, President & CEO, Economic Development Winnipeg (Tourism Winnipeg)

"Thousands of farms, food processing facilities, educational institutions, agricultural events and skilled training programs provide a strong basis for further growth... By capitalizing on existing opportunities, we can significantly expand our value-added offerings, further solidifying ourselves as a top agritourism destination."

- The Honourable Jeremy Harrison, Minister Responsible for Tourism Saskatchewan

"Saskatchewan's agritourism industry is poised to grow like never before... With world-class agricultural leadership and industry strength, Manitoba and Saskatchewan have the potential to become leading agritourism destinations on a global scale."

- Jonathan Potts, CEO, Tourism Saskatchewan

"The proposed initiatives - ranging from educational programming and farm visits to unique conference itineraries and Indigenous agritourism experiences - underscore the diverse potential of our agritourism sector. We are committed to working closely with our partners to realize this vision and look forward to the positive impact it will bring to our regions."

- Steph Clovechok, CEO, Discover Saskatoon

"Together with Tourism Saskatchewan and Travel Manitoba, we're excited to showcase the region's agricultural heritage and culinary excellence while fostering a thriving, interconnected community."

- Jennifer Johnson, Deputy City Manager of Communications, Service Regina & Tourism

Investment potential

The Field to Fork corridor presents significant potential for tourism growth and investment, leveraging the strong agricultural sectors of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Key investment insights include:

- Manitoba's agriculture and agri-food sector directly contributes 7.2% of provincial GDP and 5.1% of provincial jobs (37,015 direct jobs in 2023).

- In 2022, Manitoba's Agriculture and Agrifood sector contributed $4.92B to the economy.

- Saskatchewan's agricultural exports reached a record $20.2 billion in 2023, accounting for 40% of total provincial exports.

- The global agritourism market is valued at approximately $65.6 billion USD (2023) and is projected to reach $176.6 billion USD by 2038.

- Canada's agritourism market is valued at approximately $800 million USD (2021), with projected growth to $1.8 billion USD by 2028.

- The sector is expected to create 140,250 direct and indirect jobs in Canada by 2028.

Potential opportunities in this corridor include:

- Development of new agritourism experiences and attractions

- Enhancement of rural infrastructure to support tourism

- Creation of farm stay accommodations

- Investment in food processing and industrial agriculture tours

- Development of culinary trails and passes

- Creation of educational programs and facilities

Current Investment in the Corridor

- Travel Manitoba's Tourism Innovation and Recovery Fund (TIRF) provided $168,675 to eight operators for new and expanded agritourism experiences in 2021/22.

- The Winter Tourism Development Fund (a partnership between Travel Manitoba and PrairiesCan) provided $198,999 to two agritourism operators in 2022/23.

- Tourism Saskatchewan's Diversification Funding Program supports market-ready operators to develop new experiences, with up to $40,000 available per project.

For detailed information on investment prospects in this corridor, please contact:

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development

Destination Canada

horsnell.jennifer@destinationcanada.com

250-717-6732

Investment potential

The Field to Fork corridor presents significant potential for tourism growth and investment, leveraging the strong agricultural sectors of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Key investment insights include:

- Manitoba's agriculture and agri-food sector directly contributes 7.2% of provincial GDP and 5.1% of provincial jobs (37,015 direct jobs in 2023).

- In 2022, Manitoba's Agriculture and Agrifood sector contributed $4.92B to the economy.

- Saskatchewan's agricultural exports reached a record $20.2 billion in 2023, accounting for 40% of total provincial exports.

- The global agritourism market is valued at approximately $65.6 billion USD (2023) and is projected to reach $176.6 billion USD by 2038.

- Canada's agritourism market is valued at approximately $800 million USD (2021), with projected growth to $1.8 billion USD by 2028.

- The sector is expected to create 140,250 direct and indirect jobs in Canada by 2028.

Potential opportunities in this corridor include:

- Development of new agritourism experiences and attractions

- Enhancement of rural infrastructure to support tourism

- Creation of farm stay accommodations

- Investment in food processing and industrial agriculture tours

- Development of culinary trails and passes

- Creation of educational programs and facilities

Current Investment in the Corridor

- Travel Manitoba's Tourism Innovation and Recovery Fund (TIRF) provided $168,675 to eight operators for new and expanded agritourism experiences in 2021/22.

- The Winter Tourism Development Fund (a partnership between Travel Manitoba and PrairiesCan) provided $198,999 to two agritourism operators in 2022/23.

- Tourism Saskatchewan's Diversification Funding Program supports market-ready operators to develop new experiences, with up to $40,000 available per project.

For detailed information on investment prospects in this corridor, please contact:

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development

Destination Canada

horsnell.jennifer@destinationcanada.com

250-717-6732

Resources

- Visit the Knowledge Hub for case studies and more

- Find the latest updates

- Visit TourismScapes for information on this Corridor

Resources

- Visit the Knowledge Hub for case studies and more

- Find the latest updates

- Visit TourismScapes for information on this Corridor

Get involved

To learn more about how you can be involved in the Corridor, including partnerships and investor opportunities, community engagement initiatives, and volunteer opportunities, please contact us.

To contact the Corridor team directly:

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development

Destination Canada

horsnell.jennifer@destinationcanada.com

250-717-6732

Heather Blouin

Industry Development Consultant

Tourism Saskatchewan

heather.blouin@tourismsask.com

306-787-2825

Samantha Dawson

Specialist, Destination Management

Travel Manitoba

sadawson@travelmanitoba.com

204-296-9735

Get involved

To learn more about how you can be involved in the Corridor, including partnerships and investor opportunities, community engagement initiatives, and volunteer opportunities, please contact us.

To contact the Corridor team directly:

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development

Destination Canada

horsnell.jennifer@destinationcanada.com

250-717-6732

Heather Blouin

Industry Development Consultant

Tourism Saskatchewan

heather.blouin@tourismsask.com

306-787-2825

Samantha Dawson

Specialist, Destination Management

Travel Manitoba

sadawson@travelmanitoba.com

204-296-9735

General inquiries contact

If you have any questions, please feel free to reach out to either Erica or Jennifer for further details.

Newsletter sign-up

Stay connected with the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program.

Social Media links

Follow the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program on social media.

Eastern Region

Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island

Erica D'Souza

Senior Director, Destination Development

dsouza.erica@destinationcanada.com

Western and Northern Region

British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development

General inquiries contact

If you have any questions, please feel free to reach out to either Erica or Jennifer for further details.

Newsletter sign-up

Stay connected with the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program.

Social Media links

Follow the Tourism Corridor Strategy Program on social media.

Eastern Region

Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island

Erica D'Souza

Senior Director, Destination Development

dsouza.erica@destinationcanada.com

Western and Northern Region

British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut

Jennifer Horsnell

Senior Director, Destination Development